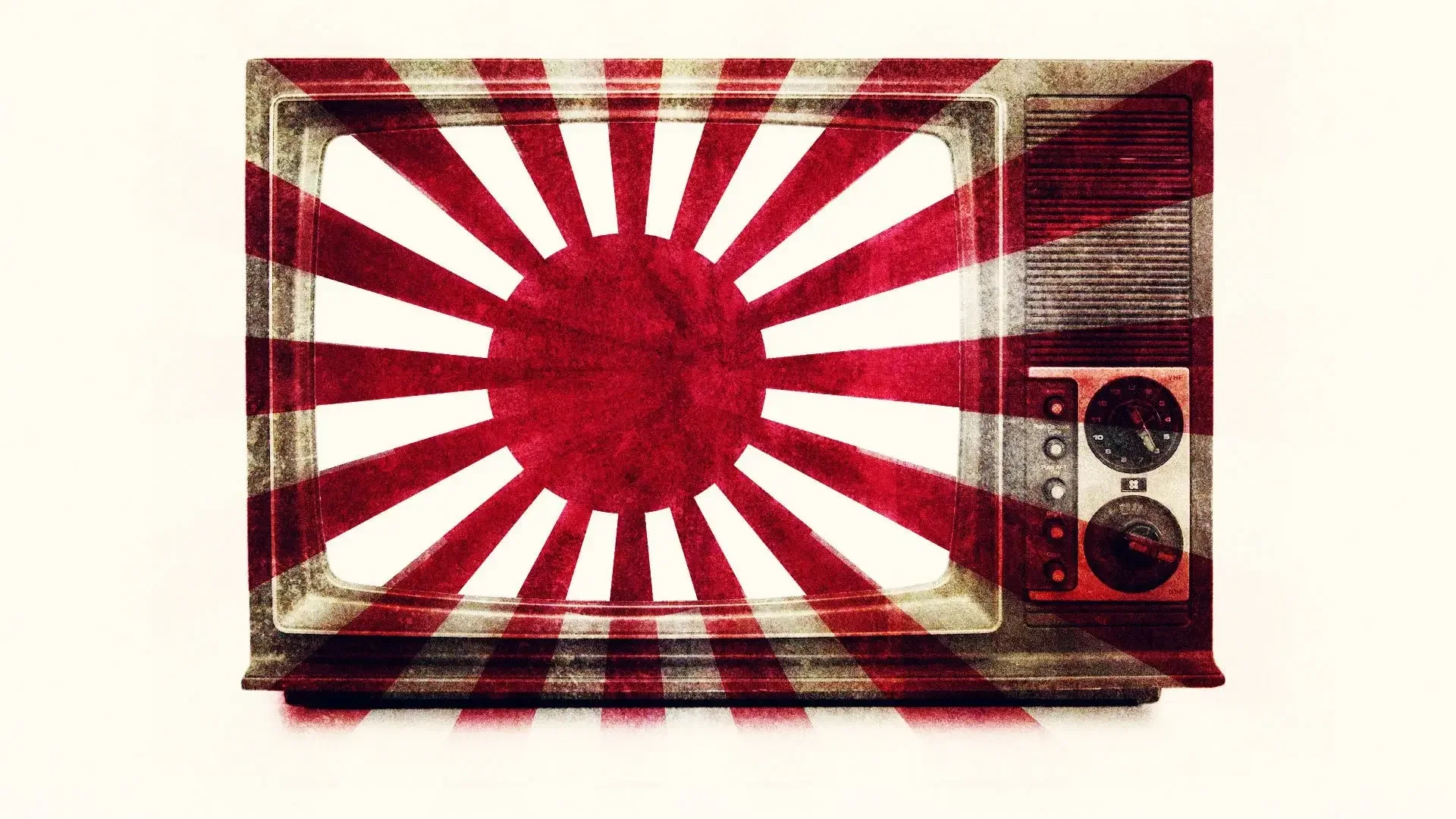

Shifting Sands: The New Divide in Japanese Politics

A high-level Japanese conference revealed a stressful truth: politics is no longer about wealth, but dangerous historical identity issues that threaten both business and public discourse.

Why Historical Issues, Not Wealth, Define Japan's Political Landscape Today

A few months ago, I accepted an invitation to chair a political panel at a high-level conference hosted by a major Japanese company—a firm with whom I'd previously enjoyed excellent loyalty and support. What I experienced, however, was incredibly stressful and eye-opening. It quickly revealed the new, defining dividing line in Japanese politics: it is all about where you stand on 'historical issues,' not where you stand on wealth distribution.

For those of us accustomed to the traditional 'right' vs. 'left' battle over economics, this focus is both strange and profoundly dangerous. For any public-facing individual, the political tightrope walk is perilous: you risk being branded an apologist for war crimes, or, conversely, being excluded from important relationships with the Japanese elite for being perceived as 'anti-Japan.'

This quandary is acutely felt by business people. Though they often tell themselves that politics has no bearing on their pursuit of profit, in Japan, relationships count. Your stance on sensitive issues like the Nanjing massacre can, I increasingly believe, directly impact your business prospects. You are essentially forced to confront these debates, as your statements are taken as a powerful sign of whether you are 'in' or 'out.'

My stress levels skyrocketed when the conference opened with a patriotic video and an announcement that “all members of this conference are supporters of the Abe administration.” The political environment has become far more difficult, marked by moves like the Abe cabinet’s visits to the Yasukuni shrine, intentions to revise the anti-war Article 9, and discussions about rescinding the Kono statement (acknowledging wartime sex-slavery).

The pervasive pro-Abe message prompted an urge to self-censor, fearing I would offend my powerful hosts. In the end, I overcompensated and was overly aggressive with the panelists. Yet, the experience clarified one thing: the central political debate was not about the obvious winners and losers of Abenomics (the stock market vs. everyone else), but purely about GDP growth. There was no discussion of economic fairness or redistribution, and tragically, no genuine opposition voices were present. The panel offered only shades of right-wing opinion, all seemingly outbidding each other to be nationalistic.

I believe this highlights how critical identity politics has become, with 'us and them divisions' re-emerging under economic stress. The increasing willingness of politicians to raise revisionist historical comments—once a vote-loser—suggests that Japan’s political centre has moved to the right.

Furthermore, an event with explicit ideological goals, like supporting a specific party, leads to flawed analysis and potentially bad decisions. Criticism was discouraged in favour of 'positive suggestions.' This intellectual rigidity—stuck in a Reagan-Thatcher time-warp—meant nobody confronted the structural problems: the snobbishness, elitism, and quasi-monopolistic vested interests that block new businesses far more than labour laws do.

I welcome a sincere, objective engagement with history, but this conference was not it. Even the presence of a respected foreign anchor felt like a cynical attempt to provide a veneer of intellectual respectability. His move to cut me off when I raised a difficult question perfectly encapsulated the environment. The concluding remarks, ironically, emphasized the importance of homogeneousness to Japan, despite the obligatory mentions of diversity. That pretty much sums things up.